It was the game on Saturday 7 November when Burnley were away at Wolves that something unusual happened. The minute the game ended the sound of mowers filled the emptying stadium and out they came to cut the grass. Nothing unusual about cutting grass on a football pitch but people looked and stared; for very rarely do the mowers come out immediately after a game and set to work.

The Wolves manager Kenny Jackett had deliberately left the grass long for the match as a ploy to slow the speed at which Burnley could break from defence to midfield, or midfield to attack, and in particular it was a ploy to slow down the through-balls that he’d seen being fed to striker Andre Gray in previous games. Gray was fast and had hitherto scored several goals following threaded balls that he could latch onto.

After the game all the talk was of what a dead pitch it was, the ball visibly slowing and fading and Burnley player Joey Barton commented that passes he made that normally reached the target, in this game simply died on the turf.

As a result the game was a sterile 0-0 draw with little of note to report on, minimal if any excitement, and bored spectators. In the first half Burnley had a few shots; in the second half Wolves had a few shots. Nothing else happened and everyone went home – except the groundstaff – cutting the grass. The Jackett masterplan had worked.

If it did one thing it illustrated how the state of a pitch can affect a game, not exactly rocket science, but it further showed that a manager and a groundstaff can shape a pitch to be a certain way and then that will affect an outcome.

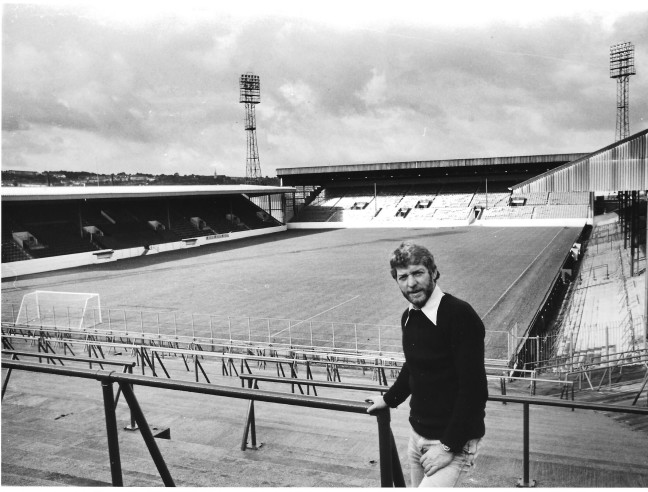

Roy Oldfield can remember pitches with mud, with snow, with puddles, with long grass or short grass, he can remember pitches that were a swamp on one side and dry on the other but he was intrigued by the deliberate ploy of leaving the grass long at Wolves. Roy was a groundsman who belonged to a time when there were no Desso pitches, no pitches that were like bowling greens all year round.

What we see on a matchday is just the tip of the iceberg of the football industry. And that too is a phrase that Roy would never have heard decades ago. The football industry (and it would be interesting to identify who first used this description of what basically used to be such a simple, uncomplicated game), is now worth billions of pounds. And yet behind the scenes unknown to us all, a groundstaff and their mowers can have such a profound influence.

So: we see the galacticos, the star names, the big-name managers and even players lower down the leagues on wages of thousands of pounds a week. We see SKY sports, the newspapers filled with news and features and gossip, Match of the Day, glossy magazines, live games and all the glamour and razzmatazz of the game; it’s reached saturation point.

Yet there is a small army of people behind the scenes, and always has been, that we rarely see that keeps the whole circus ticking over. Roy Oldfield was once a part of all this, one of the countless people that played such an important part, one of the almost anonymous unsung heroes, never in the front line, never seeking publicity and in Roy’s case just happy to be left alone to get on with his job. There were times when the pitch had been cut up so badly during a game that if it was a night game it could be 2 in the morning before he got home after doing all the repairs. He is a modest and unassuming man but ask him a question about his time being a groundsman and the face crinkles and creases into a smile and he’ll more than likely begin with , ‘I’ll just tell you a little story,’ and he’s still talking half an hour later.

He’s in his 80s now but apart from getting a bit short of breathe sometimes is fit and well. His wife Eva died several years ago so he lives now in a spruce and trim little bungalow on the outskirts of Burnley. It was the second time I went to see him that we looked out of the kitchen window at his back garden on a grey, damp day. .

‘Do you want a brew?’ he asked, so on went the kettle.

‘That’s a bit of Turf Moor in the corner over there,’ he said and he pointed to a part of the garden where there was a patch of lawn. ‘That’s from grass seed from Turf Moor,’ he added with a smile. ‘I used to let players have grass seed as well. Some of them would ask what I should do with it. They had no idea. Scatter it on any bare patches and believe it or not it will grow, I told them.’

Clearly even though it is over 20 years since he left Turf Moor that little bit of grass in his garden means something, a reminder of his days there, of good times and bad and all the people he met over the years. He was known for the quality of his pitches and well respected; many a visiting manager after a game came to his room to thank him. But for a groundsman there is no limelight, no fame or fortune. Produce a beautiful surface today with all the modern scientific aids, machines, sun lamps and Desso pitches, and it is almost taken for granted. 30 years and 40 years ago these guys had to really work at it.

A fading newspaper article that goes back to the 80s is stuck into his scrapbook with sellotape.

Clarets fans may criticise the team, from time to time, they may criticise the manager and directors, but few could complain about the Turf Moor pitch. The pitch, which measures almost two acres, has been the responsibility of groundsman Roy Oldfield for 17 seasons, save for a spell of about four years away from the club. Roy’s job is as unpredictable as the weather and he avidly watches the forecasts on TV to try to be one step ahead of his greatest opponent.

‘The weather is my enemy, not the players,’ he says.

The Monday morning after a Saturday home game sees Liverpool-born Ro, 55, on the pitch with his assistants. Their first job is to try to patch up the turf after it has been cut up by the players on Saturday afternoon and that can take up to six hours if it is in a really bad way. Tuesday’s main job is to roll the pitch and in the summer trim the grass if necessary to ensure that it is as flat as possible. The pitch is then spiked to a depth of about six inches to encourage drainage and allow air to get to the grass roots.

On Friday the grass gets a trim although Roy does not believe in giving it a proper scalping. “I do not cut it very short because it helps to keep the grass and you need it in the winter months,” he said.

Roy is at Turf Moor at 8.45 a.m. on Saturday to carry out a few pre-match duties such as checking the pitch once more and the nets. The next task is for Roy to mark out the pitch. This is usually done as late as possible on a matchday. He then checks the players’ changing rooms and cleans out the dug-outs, furnishing them with cushions and the substitute cards.

The referee usually arrives around lunchtime and Roy is there to welcome him with a cup of tea and a warm welcome. Then he is ready for the kick-off. When it’s all over he checks the changing rooms to make sure the lights and taps are all off and if there is a forecast of frost he will stay until around 7.30 to roll the pitch.

Sunday is usually a day off and a day of rest unless there is a mid-week match at Turf Moor and then the whole process starts again. It all sounds relatively straightforward, until you take the weather into consideration. Roy has nightmares about waking up on a Saturday to find a heavy downpour. A deluge just before a game can be a killer.

“You have got a very hard job to get the water away. You have got to fork it and spike it and while the teams are travelling and the supporters are on their way you are doing your best to get the water off the surface.”

Snow is the other blight although the ground staff can roll tat out and mark the lines in either blue or red. Basically, Roy and his team will do anything to make sure the game goes ahead.

“If it is called off you feel very disappointed. You know it is not your fault and you have done your best. You always prepare for what might happen. If there is a possibility of snow you get the referee in early to make an inspection.”

Roy is now working under his twelfth manager at Turf Moor. He was first employed when Jimmy Adamson held the post replacing John Jameson who taught him the ins and outs of the job. During his time at Burnley he has met some of the greatest names in the game including Kevin Keegan, Denis Law, and Kenny Dalglish.

But his meeting with one man stands out in his memory. “The most interesting man I have met was Bill Shankly. He talked such sense. One of the most pleasing things about this game is the people you meet. I read so much about the bad side of football but there are more good people than bad in it.”

He generally finds that the conditions of his pitch meets with approval all round. “The weather can make me a bit difficult at times but they don’t complain.”

Sunday November 22, 2015, at Turf Moor: rain in the preceding couple of weeks had been merciless but the world had had a few days to dry out. Then there had been frosts and snitterings of snow. Years ago by November pitches everywhere in all the leagues would have been showing signs of wear and tear. The centre circle and areas around it would most certainly have been patchy or even bare of grass perhaps, the goalmouths most certainly would. By the end of a game in the rain those areas would have been patches of mud and players would come off the field covered in it. If your shorts were clean and un-muddied in those days fans would wonder why and question a player’s commitment and ability to get stuck in.

But on November 22, 2015, the playing surface at Turf Moor was pristine, green, not a sign of a bare patch anywhere and when was the last time anyone had seen mud at a game? When was the last time we had seen players leave the field blackened and caked in mud with shorts that would need a power-wash.

The wonders of Desso: stadium designer and expert Paul Fetcher discussed them in his comprehensive book ‘The Seven Golden Secrets of a Successful Stadium.

‘The best pitches I’ve come across in the last 15 years are without doubt the tried and tested and loved Desso Grassmaster pitches. I installed the first one in this country at the Alfred McAlpine Stadium in 1995. A strong and stable pitch was needed to accommodate football on Saturdays and Rugby League the following Sunday. Desso promised that three games a week on the pitch were possible. The Huddersfield pitch had a 10-year warranty and was still looking good some 15 years later in 2010.

The Desso Grassmaster solution is quite simple. Mixing a synthetic pitch with a grass-rooted pitch, it works a treat. The Desso website explains:

Desso Grassmaster is a sports field of 100% natural grass reinforced with Desso synthetic grass fibres injected 20cm deep into the pitch. The unique element of this patented reinforced natural grass system is the 20million artificial grass fibres injected 20cm deep into the pitch. During the growing process, the roots of the natural grass entwine with the synthetic grass fibres and anchor the turf into a stable and even field. In this way the natural grass fibres are well protected against tackles and sliding. Moreover it ensures better drainage of the [pitch. Despite the fact that 3% of the pitch is made up of synthetic grass fibres, Desso GrassMaster gives players the feeling playing on a 100% natural grass pitch.

Clubs like Arsenal FC, Denver broncos, Tottenham Hotspur, RDS Anderlecht, Burnley FC and Wembley Stadium are certainly convinced of the benefits. Desso Grassmaster is authorised by both FIFA and UEFA for top competitions. The Desso Grassmaster system was also installed at the stadiums in Nelspruit and Polokwane for the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

With a Desso pitch, mowing, fertilising and watering are some of the standard tasks just as with any normal natural grass pitch. But instead of rolling the field after a match or training, it is also good to regularly perforate and ventilate a GrassMaster pitch. The pitch should be verticut and the dead grass removed. A rake can be used to open up the top layer slightly giving the algae less opportunity to grow and preventing silting up of the top layer.

The machines that inject the artificial turf into the soil are computer controlled and are designed to equip a sports field with grass fibres as efficiently as possible. These machines are too large for ordinary gardens or lawns.

At Turf Moor, according to Paul Fletcher, it was John Mallinson of Ormskirk who laid the Desso pitch at Burnley at a cost of approximately £750,000. All growth factors, light, temperature, CO2, water, air, and nourishment, can be controlled so that there is optimum grass growth under every condition. The use of artificial lighting is a huge factor in the process using Lighting Rigs. Burney FC purchased two at a cost of £17,500 each. These rigs are on wheels and are moveable so can be used anywhere on the pitch.

It is these lighting rigs that compensate for the age-old stadium problem that not enough natural light gets to all areas of the pitch to compensate for the heavy use. The damaged grass does not grow fast enough if left to its own devices especially in months when there are lower light intensities. The amount of wear then makes it impossible to maintain the quality in wintertime.

Added to all this, the growth of grass can be analysed continuously by a computerised system and steps taken that will result in a pitch that has a summer quality all year round.

Even pitch direction has its effect on grass and turf. The most favourable direction is a pitch that points 15 degrees west of due north. This allows maximum sunlight onto the playing surface all through the year. This is helped greatly if translucent panels are used to cover sections of the west, east and south roofs.

To mark the lines a special marking vehicle sprays a special paint onto the Desso pitch. The paint is resistant to water when it has dried after an hour. It is following growth and mowing a couple of times that these lines will disappear.

Roy Oldfield had no computerised scientific aids, certainly no Desso pitch, no undersoil heating, no lighting rigs. At certain times of year one strip of the Turf Moor pitch in the coldest weather was permanently frozen at worst, or remained frosty at best. He had fertiliser, sand, spare topsoil and a lot of manual labour provided by apprentices. Verticutting was an unknown to him.

The absolutely immaculate green pitch that Burnley played on at Turf Moor for the November Brighton game would have had players of earlier decades wide-eyed and envious. But they never complained at what they had to play on. For them it was normal, be it mud or ice. The likes of John Connelly, Jimmy McIlroy and Ray Pointer played on surfaces that varied so much and so badly that today the games would be abandoned. At Valley Parade on February 20th they played an FA Cup-tie on pure mud. It was so bad that players became unrecognisable and when Burnley scored two late goals to equalise barely a spectator knew who had scored.

The game was a perfect example of how a desperately poor pitch could act as a leveller and affect the outcome of a game between two sides one of which was so much better than the other. Jimmy McIlroy remarked that as soon as he saw the pitch he knew any quality team would be badly handicapped. The ground was so wet and muddy they could not even walk out onto it before the game without ruining shoes, socks and trousers. It resembled a sandy beach glistening just after the tide had receded. Manager Harry Potts wore wellingtons to carry out a pitch inspection. After half-an-hour Burnley’s superiority had evaporated and 22 players slogged it out on a mudbath and churned up surface. It was quite simply a game that would never have started today

Just three days later they played on an icebound pitch that was downright dangerous with patches of real ice, particularly down the flank by the Bob Lord Stand, a strip that never saw the sun. I was actually at this game (and had also attended the first game at Bradford) Ray Pointer slid into the perimeter wall and hit his head. All players slipped and slid, turning quickly was a lottery. Ray Pointer’s goal came from a Brian Pilkington run that took him half the length of the pitch on a part of the pitch that I remember looked like Antarctica, making it a miracle that he kept his feet. It was another game in conditions that would never have been tolerated today, but having said that; today’s undersoil heating would have solved the problem.

Some years before that, in the 1946/47 season, games were played in even worse conditions. This was the winter of the great freeze that went on and on blanketing the country with endless snow and ice. The FA Cup games between Middlesbrough and Burnley went ahead, the replay on March 4, 1947. Contemporary reports talked of jagged ice corners and ridges that had to be levelled and the application of brine and sand. Men with picks and shovels did their best to make a surface on which the game could go ahead. For the record Burnley won 1-0 to a hotly disputed goal.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, Thomas Taw’s wonderful book Football’s War and Peace, the Tumultuous Season of 1946/47 describes a game at Burnley:

‘The winter had one last sting in its tail. Forget November when Leicester and Burnley sank in the scrum of a Turf Moor mudbath, or March when Burnley and Middlesbrough slugged out a cup-tie in extra time on a jagged ice field, and the many games in-between. The day the players finally collapsed was Easter Sunday, 5 April.

‘Pitiless rain which swept over Turf Moor in an incessant downpour and a high wind that rippled the waterlogged surface into miniature wave made football farcical and it was not surprising that players succumbed to the intense cold and constant soaking. Two Burnley players were carried off and three of Chesterfield’s ‘went under’ as soon as they left the pitch. Kidd was put into the hot bath complete with football kit. Ottewall collapsed into the bath.’

Before that on 16 January a league game was played at Turf Moor on a snow-covered pitch. Players skated all over the place. Turning quickly was impossible. Conditions were described as treacherous and an icy wind blowing across the ground added to the problems of staying upright. Throughout the game players slipped and fell. Burnley won 2-1 but the Chelsea goal was a result of defenders not being able to turn quickly on the surface. Countless games like this were played throughout the divisions year after year.

Even into the 70s there were truly dire pitches especially the Derby County Baseball ground surface that game after game was just inch-deep cloying mud that covered most of the playing surface. Former player Mark Proctor well remembers it:

‘The Baseball Ground was notorious. I played on it and it resembled the surface of the moon; there wasn’t one blade of grass on it. But you just had to get on with it, and to be fair, it was the same for both sets of players. It wasn’t a big deal. Before my time Brian Clough deliberately used to water the pitch at Derby when he was the manager and it ended up looking like a mudbath.

‘That said, I can remember Jack Charlton watering the pitch at Middlesbrough before a big FA Cup-tie – I think it was Arsenal in the 1970s. Managers would try to produce a surface that the opposition would struggle to cope with.

‘The safety of players is paramount now; I don’t think they were quite as strict 30 years ago. You could get hurt if you fell awkwardly on a frozen pitch. You could also get hurt of you fell playing on the artificial surfaces that came into the game around that time. QPR had one and so did Oldham Athletic. You used to get some awful skin burns that took ages to clear up.’

Former Burnley player Paul Fletcher also well remembers the old Derby pitch. ‘We played there one Saturday when it was really bad, not just mud but inches of standing water everywhere. Doug Collins was captain that day and when the coin was tossed to choose which way to play he jokingly told the referee: “We’ll kick off towards the shallow end.”

Mark Proctor continued: ‘The aspect of the game that has changed hugely over the last 20-odd years is the quality of the playing surfaces. Pitches are far better now than they were in my day; the playing surfaces are pristine these days, like bowling greens. Players these days are lucky that they nearly always train and play on good pitches; they learn their trade on superb surfaces and they don’t know any different.’

And yet the new perfect Desso pitches are not without their accompanying problems. The question now being asked is what is the physical impact on players? They have undoubtedly aided the quality of football and the speed at which it is now played. The ball runs and bounces consistently true. But no less a person than England manager Roy Hodgson described them as ‘a snake in the grass’ with a downside that they are hard surfaces to play on so that players feel the shock of impact on their bodies and feel it more in their joints and tendons. The theory is that on a hard surface energy is delivered back to the limbs more quickly than on a softer pitch where the softness, absorbs the energy. As yet, however, there is no clear research into any of this so for the moment it is supposition that there is a new category of impact injuries.

Roy Oldfield, an ‘old-school’ groundsman from three decades ago, smiles wistfully at all of this when I describe to him the way in which the top clubs now take into such detailed account the pitch surface; monitoring the soil and air temperatures, taking soil samples, keeping a scientifically controlled check on nutrient levels, and the height and cut of the pitch. The groundsman today plays a far greater role than ever before in determining how a team and an individual can play inasmuch as a surface can be prepared that actually aids a team.