I’d been on another visit to see Roy and he had delved into his cupboards to find more of his small collection of memorabilia. The rain was still coming down in buckets. I’d driven through Mytholmroyd and Hebden Bridge where the River Calder had wreaked havoc and destroyed two town centres with waters that rose five feet high into the interiors of shops and houses. It was a chastening sight, seeing people’s possessions piled high in sodden heaps on the pavements waiting for collection and disposal.

‘There’ll be groundsmen up and down the land in the lower leagues tearing their hair out,’ I said to him. ‘Maybe even some with Championship teams that don’t have Desso pitches.’ Ironically, the Blackburn game was postponed the following day because of a waterlogged pitch at Newport. The Cup game at Eastleigh against Bolton Wanderers was played on a surface that looked like a cabbage patch.

The groundsman we both felt sorry for was Dave Mitchell at Carlisle United. The December rains and floods up in Cumbria had completely submerged the Brunton Park pitch and not for the first time. It had already happened once in 2005 and aerial views of the devastated club had featured in most national newspapers. When the floods subsided and the muddied rubbish-strewn pitch emerged, a goldfish was found floundering in the remains of a puddle in one of the goalmouths.

This time the water had been even deeper, but on the day I met Roy again it had at last receded, the debris and filth had been cleared by supporters and volunteers and the levelled mud was ready for new turf to arrive. Meanwhile the team was playing its home games at the nearest grounds that could accommodate them with the next game due to be played at Blackpool. Roy certainly had his problems to contend with, but nothing was ever as bad as this.

‘My glass is always half empty,’ said Mitchell in an interview.

It made me wonder if this was the standard creed of most groundsmen. Roy said not; but when Mitchell added that, ‘there’s only one winner where the weather is concerned,’ it was an echo of Roy’s own experience who agreed with it totally. Mitchell was still lacking power for the irrigation pumps and was hoping to stage the first game of the year at the end of January. This time it wasn’t one flopping goldfish they found in a remaining shrinking pond, but three Koi Carp that were astonishingly re-united with their owner.

Roy had found an old Press picture of himself, Jimmy Adamson, John Jameson and assistant Ian Rawson standing together at Gawthorpe laughing and chatting. Bob Lord was passing by when the picture was taken and as he walked by turned his head and muttered with the faintest of smiles, ‘They could grow grass in concrete, these lads.’

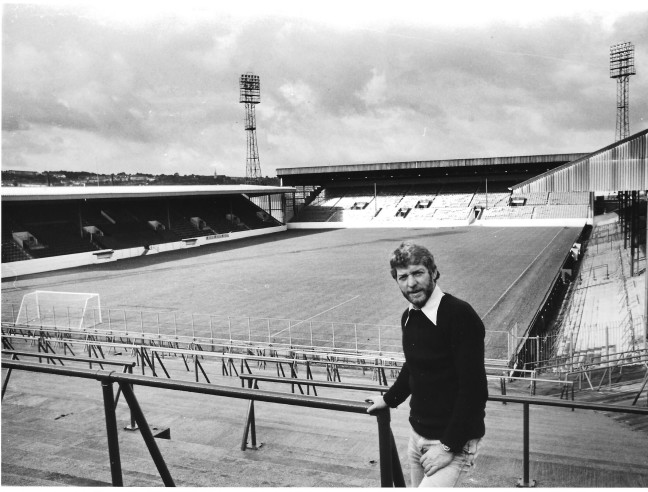

On his first day alone and in charge, he remembered how nervous he had been. If anything went wrong it would be his fault and him alone to blame, but from his seat on the bench by the players’ tunnel he saw a remarkable season unfold in 1972/73.

‘Some refs were just so fussy,’ he recalled. ‘Some were bossy and officious. Had I done this, had I done that, was this measurement correct, were the nets secure, was the penalty spot correct, had I checked this, had I checked that? Some of them were a pleasure to talk to and they were the ones that always came in for a brew and a chat. Some of them you were glad to see the back of. But it was part of my job. I was a bag of nerves the first time I was ever in charge on my own.’

Other than those Saturday pre-match worries he could pinch himself and say what a wonderful job this was especially on a warm, summer’s day with the sun and blue sky overhead. On Gawthorpe days in his T-shirt, shorts and trainers was there any better job than driving the tractor with the warm sun on his back. He preferred not to think about the cold days when there was incessant drizzle and grey skies with the rain running down the back of his neck as he worked outdoors.

In fine weather Gawthorpe was a beautiful area. Harry Potts used to rub his hands together and tell the players there was no finer place to be. Little Switzerland he used to call it when the snow had fallen.

‘Gawthorpe Hall is something like 400 years old,’ he explained, ‘and had belonged to the Shuttleworth family and now belongs to the National trust and they run it with Lancashire County Council. Close by is the river and the other side of the river is the training ground. Around all of that is a mass of wild life and birdlife. There was one time I remember and a party of Germans arrived to see the Hall but they came into the wrong entrance and ended up in the training area.

“Where is the Hall,” they asked. “We come to see the Hall and the Lord and Lady.”

‘Somewhere we made ourselves understood, I managed to show them where the Hall was and told them it was where I lived.’

‘There was always a bit of fun at Gawthorpe as well when the livestock from the neighbouring farm used to break in through the fencing. All the apprentices were summoned to help round them up and I’d get up on the tractor and ride round like John Wayne shouting and hollering to get them back to where they belonged.’

It was maybe when Roy was trying to grow normal grass, not in concrete, that one day quite out of the blue Brian Clough turned up on the pitch whilst Roy was working and mowing. It was the sound of the mower that had attracted Clough because he could find no-one else in the offices under the Stand. He had simply walked in, searched for the secretary Albert Maddox, looked around several empty rooms, gone out onto the pitch; called out to Roy who turned round, stopped the mower and was then quite amazed to see none other than the illustrious, instantly recognisable Brian Clough striding out bold as brass approaching him.

By this time, in ‘72/73 Clough had left Derby County where he had been for six years. His TV work had made him into a household name and a real celebrity; in fact he never seemed to be off the TV screens. But after a major confrontation about all his TV appearances with Sam Longson the chairman of Derby County, he had left the club and joined Brighton and Hove Albion with his assistant, Peter Taylor. Brighton were a lowly club but their chairman, Mike Bamber, was ambitious and in Clough saw a chance to establish his club in the bigtime. Bamber promised Clough complete freedom and it was this that appealed to Clough. For his first game in charge an extra 10,000 people crowded into the ground.

He was there for just nine months, during that short time making all kinds of promises, but then upped and left in July 1974 to take the Leeds United job. But in the meantime he called in on Burnley and took Roy by surprise.

He wanted two Burnley players, Harry Wilson and Ronnie Welch and had come to see Adamson and Lord about them. That was the Clough style, just call in unannounced if he wanted someone’s player but neither the secretary Albert Maddox, Adamson or Lord, was anywhere to be found.

‘Where is everybody?’ Clough asked in his inimitable voice, clearly exasperated only to learn from Roy that they were probably all out having some lunch.

‘Lunch… I don’t get any bloody lunch,’ Clough announced. ‘What time does this bloody office open? Ah’ll wait ‘til they open.’

‘Anyway, I calmed him down, took Clough under my wing and offered him the inevitable brew in my little room. While he sat sipping that I went across the road to the nearby chippy and got us a pie and some chips each. We sat in there and chatted away about football and life until Clough went off once again to search for anyone who could sell him Wilson and Welch.’

Whether or not Clough found anyone to talk to that particular day, Roy has no recollection, but eventually a deal was done for the two of them at a reported fee of £70,000 which was a good figure for those days; they weren’t exactly established, big-name players. Lord was no doubt delighted and Adamson clearly had no firm plans for either of them.

The two players arrived at the Goldstone in December ’73 with Wilson making the most appearances in the number 3 shirt. He had played only had a handful of games at Burnley but played 146 times for Brighton and scored four goals. Welch made just 40 appearances for Brighton and just one for Burnley.

For the new season there would be no Big Steve Kindon to drive Roy mad. Manager Adamson sold him to Wolves. Kindon was devastated if not furious at the time, maintaining ever since that it came out of the blue and that Adamson had continually assured him he was building a team around his power. Since then he has always joked: ‘I was so mad I just wanted to finish with football, so I signed for Wolves.’

‘But at least my pitch was safer,’ joked Roy. ‘Nobody slid on it like Steve or slid as far. Nobody made ruts as big as he did. In those days they wore longer studs, in fact I used to ask him did he wear stilts under his boots; he made so much a mess of the pitch.

‘Bloody hell Steve,’ I’d say to him, ‘just look at the mess you’ve made on my pitch again, just look what you’re doing.’ But he’d just laugh and walk away.’ Poor Roy had no idea that a few years later Steve would return to the club.

Another one to leave was winger Dave Thomas a huge crowd favourite who would go on to have a glittering career at QPR and then Everton and England.

‘He was brilliant,’ said Roy, ‘and we loved to see him flying down the wing. A lot of us still wonder why he had to be sold.’

He was sold in fact because he and Jimmy Adamson did not see eye to eye. He was a terrifically exciting player and could beat a full-back and cross a ball a dozen times and more in a game; but Adamson wanted him to work and tackle as well and this was not his natural game. He piled up a number of appearances but then fell out of favour just before the ‘72/73 season. He was brought back and played half a dozen games but growing more and more disillusioned at the club he went on the transfer list. It didn’t help that he had lost his place following a two-game suspension and was unable to get back in the side. Whilst Thomas has always blamed Adamson for unsettling him, Adamson blamed Don Revie for turning his head with the praise he showered on him.

It was during this memorable season that a complaint from QPR immediately after a game nearly caused Roy huge problems. Ironically both clubs would win promotion that season but when QPR came to Turf Moor there were accusations of theft from the QPR dressing room. The doors of each dressing room were always locked after the teams and management had come out. Roy had the key.

The accusation after the game was that money had been stolen from one of the players. Roy was baffled, how could it have been, he had the key in his pocket. But how anyone could have broken in is baffling, he said to the QPR manager, to the police who arrived and to himself. It looked like this was going to escalate into something nasty with accusations flying back and forth until one of the QPR players came out of the dressing room.

‘It’s not been stolen,’ he told them all, and explained that the player in question had been gambling heavily on the coach. He had lost a huge amount of money so that now he was trying to cover this up and recoup his money by saying it had been stolen.

‘The QPR manager was aghast,’ Roy continued, ‘and said he’d sort it back at the club. Not long after that we received a letter of apology.’

‘Every now and then in the summer months I was still doing a bit of work for Bob Lord up at his house. The Alsatians were still there, the ones that terrified me, but his daughter Barbara with just one word of command made them sit with her instant control. I was getting a fair wage at the club but if I worked at the house Bob would slip me a few extra bob into my coat pocket. One day he came out and pulled a little wage packet out of his back pocket.

‘Just a minute,’ he said, ‘this is for you,’ and handed it to me.

‘But Mr. Chairman I’m fine. Things are quiet at the moment; you’ve already paid me for working at the club,’ I said genuinely surprised.

‘Never mind, just put this in thi pocket and say nowt,’ he replied.

I can’t say it too often, I had such a lot of respect for him; he was good to me, including getting me extra tickets for some of the big games when I needed them. He knew he could always ring me before a game if he needed anything doing or a group of his guests taken for a tour of the ground. On one such occasion it was a group of people before a game against Chelsea.

‘Yes Mr. Lord I’ll take them round,’ I answered him. ‘At the end of the tour one of them stepped forward and thanked me immensely for the tour. It was Seb Coe.’

Someone who worked alongside Roy was maintenance man Allen Rycroft and it was the smell of silage that Allen remembers even today. Grass cuttings from mowing the pitch were simply heaped up across from the back of the Longside Stand. Eventually the pile had got to huge proportions and the decision was made to shovel and barrow it all into skips to be disposed of. The apprentices were brought in and the job began. The ghastly, stomach-churning smell, however, was horrendous as much of it had turned to silage.

Allen’s job was more to do with general maintenance than work on the pitch although at times when there were tons of soil and sand to be brought in for pitch re-seeding, he was brought in to spend hours with shovels and wheelbarrows. But his work was more to do with repairs, barrier work, joinery and painting. Today, professionals and specialist lifts would be brought in to repaint the iron girders and stanchions of the stands, but in those days it was long and hazardous triple-ladders and the apprentices some of whom were clearly terrified of the heights were the ones who climbed up them.

Leave your box of sandwiches lying around and they were fair game for the apprentices to lark about with. A favourite trick if you found a dead mouse was to flatten it with a spade and then put it inside someone’s sandwich. It was very easy if you were working on the pitch to casually leave your lunchbox in the dugout. That was when it was an easy target for the dead mouse treatment.

‘And Bob Lord watched us like a hawk,’ said Allen. Like Roy he can still picture him standing at the top of the stairs in the new stand, spending more and more time at the club, arms folded, just standing and watching what everyone was doing.

‘He rarely spoke to you and you were always wary of where he might be or when he might appear, or even who he was watching. If you thought he was watching you, you got your head down and worked. He once saw me leaving early because I was going to an away game and I knew he was watching me and wondering why I was leaving. But I’d arranged to finish early and I don’t doubt he made enquiries and found out it was all above board.

‘You’d just be so careful. At Gawthorpe there was the Great Barn and before it was handed to the National Trust, it was used by the players for changing. One part of it was filled with timber and logs and I was told to take a load of it up to his house one day. As I worked unloading it all, I knew he was in the house watching, sitting in his armchair with a view of his garden. Obviously I got paid for all the work I did at the ground but Mrs. Lord came out and thanked me and handed me a decent tip, and said I’d earned it. Now immediately it occurred to me that this was perhaps some kind of test and politely refused it saying that I was already paid for the work that I did and surely this was just part of that work. If I took it would Bob Lord reprimand me perhaps? But no: Mrs. Lord insisted I took it and told me her husband had watched me working hard and wanted me to have it.

What better view of a promotion season could anyone have than from a bench by the players’ tunnel, seeing them run out before the start of a game, and then triumphantly walk back in after a winning game all smiles and joy? Such was the privilege afforded to Roy as a result of his job. There he was, up close and personal, seeing the elation of victory, the sweat of effort, the pride of brilliant performances, as well as the occasional dejection of the rare defeats.

Roy could remember a number of things. The local paper, The Burnley Express, provided a half term report on the season that was glowing in its praise. After 20 games they had only lost once. The whole town was on a high as the wins piled up. People had a smile on their faces and there was always the old story that after a win on a Saturday, production in the factories went up on a Monday morning. His old pals working at Scott’s Park had stopped grumbling and worrying. Outsiders were asking how Burnley still managed to produce such talent; Gawthorpe was a name constantly written about in the Press.

As for the players Roy could see the camaraderie, the closeness and how they enjoyed each other’s company. Fletcher and Waldron continued to be the jokers sparing no-one, be it the physio Jimmy Holland, the commercial guy Jack Butterfield or Roy himself. All of them had to watch out for the dreaded bucket of water placed over a half-open door. Equipment was frequently hidden.

Local reporter Peter Higgs wrote of the faith the players had in each other, the confidence that came with the wins, and the sheer class of the team. It was a strong and consistent team with players that had got better and better as the season progressed despite the surprise home defeat to Leyton Orient.

There was a worry that at Christmas it could all go pear-shaped with two tough away games, the first at Blackpool ironically now managed by Harry Potts and then away at Villa. Both were wins and if there was one win all season that announced that Burnley were the real deal it was the 3-0 away win at Villa. At Turf Moor Burnley had won 4-1 but after the away win the newspaper headline simply asked, Who Can Stop Burnley Now?

The Press reported that the game at Villa Park was promotion rival Villa’s big chance to catch up on Burnley, but then described that all they could hope for was to hang on to Burnley’s coat-tails, an all-conquering side that had now notched up five wins on the trot. It was a defining game with Burnley smooth yet powerful, bristling with enthusiasm and team spirit. There were crisp moves, slick skills, powerful defending and a competitive attitude to every 50:50 ball that carried all before it. And, as the last line of defence, there was goalkeeper Alan Stevenson who showed his sheer class when Villa had an occasional shot.

But Roy was like Adamson and remembered that not much more than 10 years earlier Burnley had amassed a big lead at the top of the table by April of ’62 and were clear favourites to win the title. He had been there and seen many of the games that season at the end of which they also lost a Cup Final against Spurs. Inexplicably they let the lead dwindle; they had games in hand and wasted them. Roy and thousands of supporters could only watch in disbelief as Ipswich had pipped them to the title. Adamson preached caution. Roy agreed.

Roy now saw his job as simply to help produce the best possible surface to help the team and its brilliant passing game; a surface that was acknowledged as one of the better ones in the division. The daily chores continued, spiking, rolling, mowing, replacing divots, repairing slide marks and gouges, and worrying; worrying about rain, worrying about snow and frozen surfaces; worrying when it was a particularly fussy referee that was due. And not just worrying; by the end of ’73 irritation was in its very earliest stages, irritations caused by one or two directors who began to think they could tell him to do this and mend that, or fix this and paint that in other parts of the ground. It wasn’t a huge concern at first; it was in its embryonic stage but would certainly develop further over the coming months. His workload had increased when Jeff Haley one of the groundsmen he worked with suddenly left.

Promotion was clinched in a Monday evening home game when Burnley beat Sunderland 2-0 with both goals from Paul Fletcher. ‘There were some marvellous and astonishing scenes that night,’ said Roy.

‘Bob Lord strutted around Turf Moor like he was the king of the castle. He made sure he told as many people as possible that he had always had faith in Adamson and the team,’ Roy went on. ‘And he had every right to do. He smiled and beamed and puffed his chest out and right from then until the end of the season he was just so proud. He was proud of everyone from the players, to the groundstaff right down to the laundry ladies.

‘He’d been on the board at Burnley for 21 years and he said this is the best present I could have had. On one occasion when he came into my room to see what was going on we just got to talking and told me the story that when he first got on the board the rest of them had said, “there is nowt we can do, we’ll just have to put up with him.” ‘

‘“Some people hate me,’ Bob Lord once said to me. “I tread on people’s corns,” ’

‘But you’ll never hear me saying anything like that about him. I’ll say it again. He was good to me.’

Burnley faced Liverpool in the FA Cup in ‘72/73. Roy’s loyalties were tested since he still felt an allegiance to the city where he had been born. It was a game he was looking forward to and went round the ground singing Liverpool songs that he knew.

‘Er Roy,’ said Jimmy Adamson one day with the slightest of grins when he heard him in one of the corridors singing away about Liverpool, ‘er I don’t think we want you singing those songs.’

Burnley drew the first game 0-0 but lost the replay 3-0 at Anfield.

In the League, Burnley kept going but couldn’t shake QPR off who maintained their dogged pursuit right until the final game when Burnley needed just one point away at Preston North End to win the Division Two title. Saturday, April 28, was sunny and warm, a fitting day on which to celebrate a championship. It was the day Manchester United gave Denis Law a free transfer and Bobby Charlton played his last game at Chelsea.

Burnley still needed a point from the Preston game to secure the Championship and for added spice Preston needed a point to escape relegation. As it turned out no-one was disappointed and there have always been allegations that the game whilst not quite fixed ended with a result that had everyone happy and there were moments when anyone watching could have genuinely wondered did either side really want to win the game.

Preston took the lead when Alex Bruce shot past goalkeeper Stevenson. Burnley had most of the possession passing the ball around content with the 0-0 scoreline but then Bruce forgot the script and scored for Preston. Nobody needed to worry, however, since Colin Waldron, an unlikely centre-half scorer, let fly from 25 yards and equalised 10 minutes after half-time. From that point on it was quite clear that neither side was the slightest bit interested in scoring again and the game was played out at a snail’s pace with players timidly passing the ball around in midfield for long spells. At times it was quite embarrassing with players sometimes just standing still with the ball whilst opposition players simply stood and let them, none more obvious than when Leighton James dallied by the corner flag in the final minutes with a posse of Preston players simply letting him stand with his foot on the ball. Then, it was as if the referee simply got bored of waiting for something to happen and blew the final whistle. What might also have swayed him to ignore any possible extra time were the hordes of Burnley fans along the touchlines just waiting to rush on.

‘Fix’ is certainly too strong a word; it was a boiling hot day and with half an hour to go both teams had what they needed. Perhaps we could simply say that at that point, the players quietly decided to take it easy for the rest of the afternoon but Jimmy Adamson afterwards emphatically denied that the result was pre-determined.

‘The celebrations took place four days later in a testimonial for that great full-back John Angus,’ Roy reminisced. ‘More people turned up for that game than the average for all the others. It was a real party mood with The Old Stars team playing The Young Clarets, and then the title winners took on The Millionaires, a team of players most of whom had once been at Burnley but had been sold. Willie Irvine turned up as well. He was at Halifax at the time but defied his manager’s orders not to play. Jimmy Adamson was named manager-of-the-year. Only a few months earlier in the previous season fans had been booing and jeering him. Sometimes it’s just a real pleasure and a privilege to prepare the pitch even with all the work it involves. This was one of those games.’

Bob Lord was known for his lavish dinners that he put on regularly for players, staff and special guests. The Imperial Hotel in Blackpool was his favourite location and once again he selected it to celebrate winning promotion back to the First Division.

He certainly know how lay on ‘a good do,’ said Roy. ‘He did everything with style and class at these events, from the stylish invitations sent to us all, the immaculate arrangements, the travel that was organised for you if needed, to the beautifully produced glossy 8-page programme for the evening with the claret tassel.

‘I still have mine today, Roy said. ‘The picture of Bob Lord and Jimmy Adamson holding the trophy is the first thing you see when you open it. The menu is on the first of the centre pages. Looking at it brings back such memories, the strongest of which is being there with my wife, who sadly passed away some time ago. I miss her still. I can see us at our table marvelling at the splendour of the evening and the wonderful food. Melon with Port, Scottish Smoked Salmon with lemon, Potee Bourguignonne, Grilled Fillet of Plaice, Lemon Sorbet, and still the main course was still to come. Roast Ribs of English Beef and Yorkshire Pudding with mountains of vegetables and all finished off with ice cream, fruit salad and double cream.

‘There were grand speeches and toasts and Bob Lord in his tuxedo, by then the Vice-President of the Football League, was in his element holding centre stage telling us that we were just a little village team but had won the prize. Burnley were back where they belonged he said. Then there was dancing and cabaret and believe it or not even after all that food we could have a breakfast of bacon and eggs in the Dining Room.

‘I can close my eyes,’ Roy went on, ‘and can still see us there.’

The two local newspapers, The Burnley Express and the Evening Star, both produced commemorative supplements to mark the promotion and return to Division One. The players, the chairman, the manager and his staff, the Commercial Manager Jack Butterfield, the physio Jimmy Holland, the trainer George Bray, everybody received an honourable mention, and just for once, the groundstaff members.

The role of the groundsman is to work hard and prepare the stage for the artists and the entertainers, whilst they themselves remain in the background, largely unknown, almost anonymous. Their minute in the spotlight was just one small paragraph tucked away at the bottom of a page. Such is the lot of the groundsman.

5: A grand season, said Roy

I’d been on another visit to see Roy and he had delved into his cupboards to find more of his small collection of memorabilia. The rain was still coming down in buckets. I’d driven through Mytholmroyd and Hebden Bridge where the River Calder had wreaked havoc and destroyed two town centres with waters that rose five feet high into the interiors of shops and houses. It was a chastening sight, seeing people’s possessions piled high in sodden heaps on the pavements waiting for collection and disposal.

‘There’ll be groundsmen up and down the land in the lower leagues tearing their hair out,’ I said to him. ‘Maybe even some with Championship teams that don’t have Desso pitches.’ Ironically, the Blackburn game was postponed the following day because of a waterlogged pitch at Newport. The Cup game at Eastleigh against Bolton Wanderers was played on a surface that looked like a cabbage patch.

The groundsman we both felt sorry for was Dave Mitchell at Carlisle United. The December rains and floods up in Cumbria had completely submerged the Brunton Park pitch and not for the first time. It had already happened once in 2005 and aerial views of the devastated club had featured in most national newspapers. When the floods subsided and the muddied rubbish-strewn pitch emerged, a goldfish was found floundering in the remains of a puddle in one of the goalmouths.

This time the water had been even deeper, but on the day I met Roy again it had at last receded, the debris and filth had been cleared by supporters and volunteers and the levelled mud was ready for new turf to arrive. Meanwhile the team was playing its home games at the nearest grounds that could accommodate them with the next game due to be played at Blackpool. Roy certainly had his problems to contend with, but nothing was ever as bad as this.

‘My glass is always half empty,’ said Mitchell in an interview.

It made me wonder if this was the standard creed of most groundsmen. Roy said not; but when Mitchell added that, ‘there’s only one winner where the weather is concerned,’ it was an echo of Roy’s own experience who agreed with it totally. Mitchell was still lacking power for the irrigation pumps and was hoping to stage the first game of the year at the end of January. This time it wasn’t one flopping goldfish they found in a remaining shrinking pond, but three Koi Carp that were astonishingly re-united with their owner.

Roy had found an old Press picture of himself, Jimmy Adamson, John Jameson and assistant Ian Rawson standing together at Gawthorpe laughing and chatting. Bob Lord was passing by when the picture was taken and as he walked by turned his head and muttered with the faintest of smiles, ‘They could grow grass in concrete, these lads.’

On his first day alone and in charge, he remembered how nervous he had been. If anything went wrong it would be his fault and him alone to blame, but from his seat on the bench by the players’ tunnel he saw a remarkable season unfold in 1972/73.

‘Some refs were just so fussy,’ he recalled. ‘Some were bossy and officious. Had I done this, had I done that, was this measurement correct, were the nets secure, was the penalty spot correct, had I checked this, had I checked that? Some of them were a pleasure to talk to and they were the ones that always came in for a brew and a chat. Some of them you were glad to see the back of. But it was part of my job. I was a bag of nerves the first time I was ever in charge on my own.’

Other than those Saturday pre-match worries he could pinch himself and say what a wonderful job this was especially on a warm, summer’s day with the sun and blue sky overhead. On Gawthorpe days in his T-shirt, shorts and trainers was there any better job than driving the tractor with the warm sun on his back. He preferred not to think about the cold days when there was incessant drizzle and grey skies with the rain running down the back of his neck as he worked outdoors.

In fine weather Gawthorpe was a beautiful area. Harry Potts used to rub his hands together and tell the players there was no finer place to be. Little Switzerland he used to call it when the snow had fallen.

‘Gawthorpe Hall is something like 400 years old,’ he explained, ‘and had belonged to the Shuttleworth family and now belongs to the National trust and they run it with Lancashire County Council. Close by is the river and the other side of the river is the training ground. Around all of that is a mass of wild life and birdlife. There was one time I remember and a party of Germans arrived to see the Hall but they came into the wrong entrance and ended up in the training area.

“Where is the Hall,” they asked. “We come to see the Hall and the Lord and Lady.”

‘Somewhere we made ourselves understood, I managed to show them where the Hall was and told them it was where I lived.’

‘There was always a bit of fun at Gawthorpe as well when the livestock from the neighbouring farm used to break in through the fencing. All the apprentices were summoned to help round them up and I’d get up on the tractor and ride round like John Wayne shouting and hollering to get them back to where they belonged.’

It was maybe when Roy was trying to grow normal grass, not in concrete, that one day quite out of the blue Brian Clough turned up on the pitch whilst Roy was working and mowing. It was the sound of the mower that had attracted Clough because he could find no-one else in the offices under the Stand. He had simply walked in, searched for the secretary Albert Maddox, looked around several empty rooms, gone out onto the pitch; called out to Roy who turned round, stopped the mower and was then quite amazed to see none other than the illustrious, instantly recognisable Brian Clough striding out bold as brass approaching him.

By this time, in ‘72/73 Clough had left Derby County where he had been for six years. His TV work had made him into a household name and a real celebrity; in fact he never seemed to be off the TV screens. But after a major confrontation about all his TV appearances with Sam Longson the chairman of Derby County, he had left the club and joined Brighton and Hove Albion with his assistant, Peter Taylor. Brighton were a lowly club but their chairman, Mike Bamber, was ambitious and in Clough saw a chance to establish his club in the bigtime. Bamber promised Clough complete freedom and it was this that appealed to Clough. For his first game in charge an extra 10,000 people crowded into the ground.

He was there for just nine months, during that short time making all kinds of promises, but then upped and left in July 1974 to take the Leeds United job. But in the meantime he called in on Burnley and took Roy by surprise.

He wanted two Burnley players, Harry Wilson and Ronnie Welch and had come to see Adamson and Lord about them. That was the Clough style, just call in unannounced if he wanted someone’s player but neither the secretary Albert Maddox, Adamson or Lord, was anywhere to be found.

‘Where is everybody?’ Clough asked in his inimitable voice, clearly exasperated only to learn from Roy that they were probably all out having some lunch.

‘Lunch… I don’t get any bloody lunch,’ Clough announced. ‘What time does this bloody office open? Ah’ll wait ‘til they open.’

‘Anyway, I calmed him down, took Clough under my wing and offered him the inevitable brew in my little room. While he sat sipping that I went across the road to the nearby chippy and got us a pie and some chips each. We sat in there and chatted away about football and life until Clough went off once again to search for anyone who could sell him Wilson and Welch.’

Whether or not Clough found anyone to talk to that particular day, Roy has no recollection, but eventually a deal was done for the two of them at a reported fee of £70,000 which was a good figure for those days; they weren’t exactly established, big-name players. Lord was no doubt delighted and Adamson clearly had no firm plans for either of them.

The two players arrived at the Goldstone in December ’73 with Wilson making the most appearances in the number 3 shirt. He had played only had a handful of games at Burnley but played 146 times for Brighton and scored four goals. Welch made just 40 appearances for Brighton and just one for Burnley.

For the new season there would be no Big Steve Kindon to drive Roy mad. Manager Adamson sold him to Wolves. Kindon was devastated if not furious at the time, maintaining ever since that it came out of the blue and that Adamson had continually assured him he was building a team around his power. Since then he has always joked: ‘I was so mad I just wanted to finish with football, so I signed for Wolves.’

‘But at least my pitch was safer,’ joked Roy. ‘Nobody slid on it like Steve or slid as far. Nobody made ruts as big as he did. In those days they wore longer studs, in fact I used to ask him did he wear stilts under his boots; he made so much a mess of the pitch.

‘Bloody hell Steve,’ I’d say to him, ‘just look at the mess you’ve made on my pitch again, just look what you’re doing.’ But he’d just laugh and walk away.’ Poor Roy had no idea that a few years later Steve would return to the club.

Another one to leave was winger Dave Thomas a huge crowd favourite who would go on to have a glittering career at QPR and then Everton and England.

‘He was brilliant,’ said Roy, ‘and we loved to see him flying down the wing. A lot of us still wonder why he had to be sold.’

He was sold in fact because he and Jimmy Adamson did not see eye to eye. He was a terrifically exciting player and could beat a full-back and cross a ball a dozen times and more in a game; but Adamson wanted him to work and tackle as well and this was not his natural game. He piled up a number of appearances but then fell out of favour just before the ‘72/73 season. He was brought back and played half a dozen games but growing more and more disillusioned at the club he went on the transfer list. It didn’t help that he had lost his place following a two-game suspension and was unable to get back in the side. Whilst Thomas has always blamed Adamson for unsettling him, Adamson blamed Don Revie for turning his head with the praise he showered on him.

It was during this memorable season that a complaint from QPR immediately after a game nearly caused Roy huge problems. Ironically both clubs would win promotion that season but when QPR came to Turf Moor there were accusations of theft from the QPR dressing room. The doors of each dressing room were always locked after the teams and management had come out. Roy had the key.

The accusation after the game was that money had been stolen from one of the players. Roy was baffled, how could it have been, he had the key in his pocket. But how anyone could have broken in is baffling, he said to the QPR manager, to the police who arrived and to himself. It looked like this was going to escalate into something nasty with accusations flying back and forth until one of the QPR players came out of the dressing room.

‘It’s not been stolen,’ he told them all, and explained that the player in question had been gambling heavily on the coach. He had lost a huge amount of money so that now he was trying to cover this up and recoup his money by saying it had been stolen.

‘The QPR manager was aghast,’ Roy continued, ‘and said he’d sort it back at the club. Not long after that we received a letter of apology.’

‘Every now and then in the summer months I was still doing a bit of work for Bob Lord up at his house. The Alsatians were still there, the ones that terrified me, but his daughter Barbara with just one word of command made them sit with her instant control. I was getting a fair wage at the club but if I worked at the house Bob would slip me a few extra bob into my coat pocket. One day he came out and pulled a little wage packet out of his back pocket.

‘Just a minute,’ he said, ‘this is for you,’ and handed it to me.

‘But Mr. Chairman I’m fine. Things are quiet at the moment; you’ve already paid me for working at the club,’ I said genuinely surprised.

‘Never mind, just put this in thi pocket and say nowt,’ he replied.

I can’t say it too often, I had such a lot of respect for him; he was good to me, including getting me extra tickets for some of the big games when I needed them. He knew he could always ring me before a game if he needed anything doing or a group of his guests taken for a tour of the ground. On one such occasion it was a group of people before a game against Chelsea.

‘Yes Mr. Lord I’ll take them round,’ I answered him. ‘At the end of the tour one of them stepped forward and thanked me immensely for the tour. It was Seb Coe.’

Someone who worked alongside Roy was maintenance man Allen Rycroft and it was the smell of silage that Allen remembers even today. Grass cuttings from mowing the pitch were simply heaped up across from the back of the Longside Stand. Eventually the pile had got to huge proportions and the decision was made to shovel and barrow it all into skips to be disposed of. The apprentices were brought in and the job began. The ghastly, stomach-churning smell, however, was horrendous as much of it had turned to silage.

Allen’s job was more to do with general maintenance than work on the pitch although at times when there were tons of soil and sand to be brought in for pitch re-seeding, he was brought in to spend hours with shovels and wheelbarrows. But his work was more to do with repairs, barrier work, joinery and painting. Today, professionals and specialist lifts would be brought in to repaint the iron girders and stanchions of the stands, but in those days it was long and hazardous triple-ladders and the apprentices some of whom were clearly terrified of the heights were the ones who climbed up them.

Leave your box of sandwiches lying around and they were fair game for the apprentices to lark about with. A favourite trick if you found a dead mouse was to flatten it with a spade and then put it inside someone’s sandwich. It was very easy if you were working on the pitch to casually leave your lunchbox in the dugout. That was when it was an easy target for the dead mouse treatment.

‘And Bob Lord watched us like a hawk,’ said Allen. Like Roy he can still picture him standing at the top of the stairs in the new stand, spending more and more time at the club, arms folded, just standing and watching what everyone was doing.

‘He rarely spoke to you and you were always wary of where he might be or when he might appear, or even who he was watching. If you thought he was watching you, you got your head down and worked. He once saw me leaving early because I was going to an away game and I knew he was watching me and wondering why I was leaving. But I’d arranged to finish early and I don’t doubt he made enquiries and found out it was all above board.

‘You’d just be so careful. At Gawthorpe there was the Great Barn and before it was handed to the National Trust, it was used by the players for changing. One part of it was filled with timber and logs and I was told to take a load of it up to his house one day. As I worked unloading it all, I knew he was in the house watching, sitting in his armchair with a view of his garden. Obviously I got paid for all the work I did at the ground but Mrs. Lord came out and thanked me and handed me a decent tip, and said I’d earned it. Now immediately it occurred to me that this was perhaps some kind of test and politely refused it saying that I was already paid for the work that I did and surely this was just part of that work. If I took it would Bob Lord reprimand me perhaps? But no: Mrs. Lord insisted I took it and told me her husband had watched me working hard and wanted me to have it.

What better view of a promotion season could anyone have than from a bench by the players’ tunnel, seeing them run out before the start of a game, and then triumphantly walk back in after a winning game all smiles and joy? Such was the privilege afforded to Roy as a result of his job. There he was, up close and personal, seeing the elation of victory, the sweat of effort, the pride of brilliant performances, as well as the occasional dejection of the rare defeats.

Roy could remember a number of things. The local paper, The Burnley Express, provided a half term report on the season that was glowing in its praise. After 20 games they had only lost once. The whole town was on a high as the wins piled up. People had a smile on their faces and there was always the old story that after a win on a Saturday, production in the factories went up on a Monday morning. His old pals working at Scott’s Park had stopped grumbling and worrying. Outsiders were asking how Burnley still managed to produce such talent; Gawthorpe was a name constantly written about in the Press.

As for the players Roy could see the camaraderie, the closeness and how they enjoyed each other’s company. Fletcher and Waldron continued to be the jokers sparing no-one, be it the physio Jimmy Holland, the commercial guy Jack Butterfield or Roy himself. All of them had to watch out for the dreaded bucket of water placed over a half-open door. Equipment was frequently hidden.

Local reporter Peter Higgs wrote of the faith the players had in each other, the confidence that came with the wins, and the sheer class of the team. It was a strong and consistent team with players that had got better and better as the season progressed despite the surprise home defeat to Leyton Orient.

There was a worry that at Christmas it could all go pear-shaped with two tough away games, the first at Blackpool ironically now managed by Harry Potts and then away at Villa. Both were wins and if there was one win all season that announced that Burnley were the real deal it was the 3-0 away win at Villa. At Turf Moor Burnley had won 4-1 but after the away win the newspaper headline simply asked, Who Can Stop Burnley Now?

The Press reported that the game at Villa Park was promotion rival Villa’s big chance to catch up on Burnley, but then described that all they could hope for was to hang on to Burnley’s coat-tails, an all-conquering side that had now notched up five wins on the trot. It was a defining game with Burnley smooth yet powerful, bristling with enthusiasm and team spirit. There were crisp moves, slick skills, powerful defending and a competitive attitude to every 50:50 ball that carried all before it. And, as the last line of defence, there was goalkeeper Alan Stevenson who showed his sheer class when Villa had an occasional shot.

But Roy was like Adamson and remembered that not much more than 10 years earlier Burnley had amassed a big lead at the top of the table by April of ’62 and were clear favourites to win the title. He had been there and seen many of the games that season at the end of which they also lost a Cup Final against Spurs. Inexplicably they let the lead dwindle; they had games in hand and wasted them. Roy and thousands of supporters could only watch in disbelief as Ipswich had pipped them to the title. Adamson preached caution. Roy agreed.

Roy now saw his job as simply to help produce the best possible surface to help the team and its brilliant passing game; a surface that was acknowledged as one of the better ones in the division. The daily chores continued, spiking, rolling, mowing, replacing divots, repairing slide marks and gouges, and worrying; worrying about rain, worrying about snow and frozen surfaces; worrying when it was a particularly fussy referee that was due. And not just worrying; by the end of ’73 irritation was in its very earliest stages, irritations caused by one or two directors who began to think they could tell him to do this and mend that, or fix this and paint that in other parts of the ground. It wasn’t a huge concern at first; it was in its embryonic stage but would certainly develop further over the coming months. His workload had increased when Jeff Haley one of the groundsmen he worked with suddenly left.

Promotion was clinched in a Monday evening home game when Burnley beat Sunderland 2-0 with both goals from Paul Fletcher. ‘There were some marvellous and astonishing scenes that night,’ said Roy.

‘Bob Lord strutted around Turf Moor like he was the king of the castle. He made sure he told as many people as possible that he had always had faith in Adamson and the team,’ Roy went on. ‘And he had every right to do. He smiled and beamed and puffed his chest out and right from then until the end of the season he was just so proud. He was proud of everyone from the players, to the groundstaff right down to the laundry ladies.

‘He’d been on the board at Burnley for 21 years and he said this is the best present I could have had. On one occasion when he came into my room to see what was going on we just got to talking and told me the story that when he first got on the board the rest of them had said, “there is nowt we can do, we’ll just have to put up with him.” ‘

‘“Some people hate me,’ Bob Lord once said to me. “I tread on people’s corns,” ’

‘But you’ll never hear me saying anything like that about him. I’ll say it again. He was good to me.’

Burnley faced Liverpool in the FA Cup in ‘72/73. Roy’s loyalties were tested since he still felt an allegiance to the city where he had been born. It was a game he was looking forward to and went round the ground singing Liverpool songs that he knew.

‘Er Roy,’ said Jimmy Adamson one day with the slightest of grins when he heard him in one of the corridors singing away about Liverpool, ‘er I don’t think we want you singing those songs.’

Burnley drew the first game 0-0 but lost the replay 3-0 at Anfield.

In the League, Burnley kept going but couldn’t shake QPR off who maintained their dogged pursuit right until the final game when Burnley needed just one point away at Preston North End to win the Division Two title. Saturday, April 28, was sunny and warm, a fitting day on which to celebrate a championship. It was the day Manchester United gave Denis Law a free transfer and Bobby Charlton played his last game at Chelsea.

Burnley still needed a point from the Preston game to secure the Championship and for added spice Preston needed a point to escape relegation. As it turned out no-one was disappointed and there have always been allegations that the game whilst not quite fixed ended with a result that had everyone happy and there were moments when anyone watching could have genuinely wondered did either side really want to win the game.

Preston took the lead when Alex Bruce shot past goalkeeper Stevenson. Burnley had most of the possession passing the ball around content with the 0-0 scoreline but then Bruce forgot the script and scored for Preston. Nobody needed to worry, however, since Colin Waldron, an unlikely centre-half scorer, let fly from 25 yards and equalised 10 minutes after half-time. From that point on it was quite clear that neither side was the slightest bit interested in scoring again and the game was played out at a snail’s pace with players timidly passing the ball around in midfield for long spells. At times it was quite embarrassing with players sometimes just standing still with the ball whilst opposition players simply stood and let them, none more obvious than when Leighton James dallied by the corner flag in the final minutes with a posse of Preston players simply letting him stand with his foot on the ball. Then, it was as if the referee simply got bored of waiting for something to happen and blew the final whistle. What might also have swayed him to ignore any possible extra time were the hordes of Burnley fans along the touchlines just waiting to rush on.

‘Fix’ is certainly too strong a word; it was a boiling hot day and with half an hour to go both teams had what they needed. Perhaps we could simply say that at that point, the players quietly decided to take it easy for the rest of the afternoon but Jimmy Adamson afterwards emphatically denied that the result was pre-determined.

‘The celebrations took place four days later in a testimonial for that great full-back John Angus,’ Roy reminisced. ‘More people turned up for that game than the average for all the others. It was a real party mood with The Old Stars team playing The Young Clarets, and then the title winners took on The Millionaires, a team of players most of whom had once been at Burnley but had been sold. Willie Irvine turned up as well. He was at Halifax at the time but defied his manager’s orders not to play. Jimmy Adamson was named manager-of-the-year. Only a few months earlier in the previous season fans had been booing and jeering him. Sometimes it’s just a real pleasure and a privilege to prepare the pitch even with all the work it involves. This was one of those games.’

Bob Lord was known for his lavish dinners that he put on regularly for players, staff and special guests. The Imperial Hotel in Blackpool was his favourite location and once again he selected it to celebrate winning promotion back to the First Division.

He certainly know how lay on ‘a good do,’ said Roy. ‘He did everything with style and class at these events, from the stylish invitations sent to us all, the immaculate arrangements, the travel that was organised for you if needed, to the beautifully produced glossy 8-page programme for the evening with the claret tassel.

‘I still have mine today, Roy said. ‘The picture of Bob Lord and Jimmy Adamson holding the trophy is the first thing you see when you open it. The menu is on the first of the centre pages. Looking at it brings back such memories, the strongest of which is being there with my wife, who sadly passed away some time ago. I miss her still. I can see us at our table marvelling at the splendour of the evening and the wonderful food. Melon with Port, Scottish Smoked Salmon with lemon, Potee Bourguignonne, Grilled Fillet of Plaice, Lemon Sorbet, and still the main course was still to come. Roast Ribs of English Beef and Yorkshire Pudding with mountains of vegetables and all finished off with ice cream, fruit salad and double cream.

‘There were grand speeches and toasts and Bob Lord in his tuxedo, by then the Vice-President of the Football League, was in his element holding centre stage telling us that we were just a little village team but had won the prize. Burnley were back where they belonged he said. Then there was dancing and cabaret and believe it or not even after all that food we could have a breakfast of bacon and eggs in the Dining Room.

‘I can close my eyes,’ Roy went on, ‘and can still see us there.’

The two local newspapers, The Burnley Express and the Evening Star, both produced commemorative supplements to mark the promotion and return to Division One. The players, the chairman, the manager and his staff, the Commercial Manager Jack Butterfield, the physio Jimmy Holland, the trainer George Bray, everybody received an honourable mention, and just for once, the groundstaff members.

The role of the groundsman is to work hard and prepare the stage for the artists and the entertainers, whilst they themselves remain in the background, largely unknown, almost anonymous. Their minute in the spotlight was just one small paragraph tucked away at the bottom of a page. Such is the lot of the groundsman.